It’s 1918 all over again: Will NJ learn from past pandemic mistakes?

There's still plenty to learn about the ongoing COVID-19 threat, but a Rutgers University-Camden researcher cites a number of similarities between the current crisis and the 1918 influenza pandemic that killed about 675,000 people in the United States.

Janet Golden, a professor emerita of history, said there are a few differences between the two pandemics — and it remains to be seen whether Americans have learned from past mistakes.

"We're in the very beginning of a learning process about the virus that we're confronting right now," Golden told New Jersey 101.5.

But just like the H1N1 flu virus that spread worldwide during 1918 and 1919, causing the deadliest pandemic of the century, the novel coronavirus is thriving on person-to-person spread.

To help stem the reach of the coronavirus, officials in New Jersey and nearly everywhere else in the country are advising residents to stay at home unless they're conducting essential business such as work or grocery shopping. More than 100 years ago, efforts to limit public gatherings — although not as widespread — were launched to control the flu pandemic.

"They did practice social distancing very much in 1918," Golden said. "They closed the theaters, they closed the saloons, they closed churches, some cities closed schools."

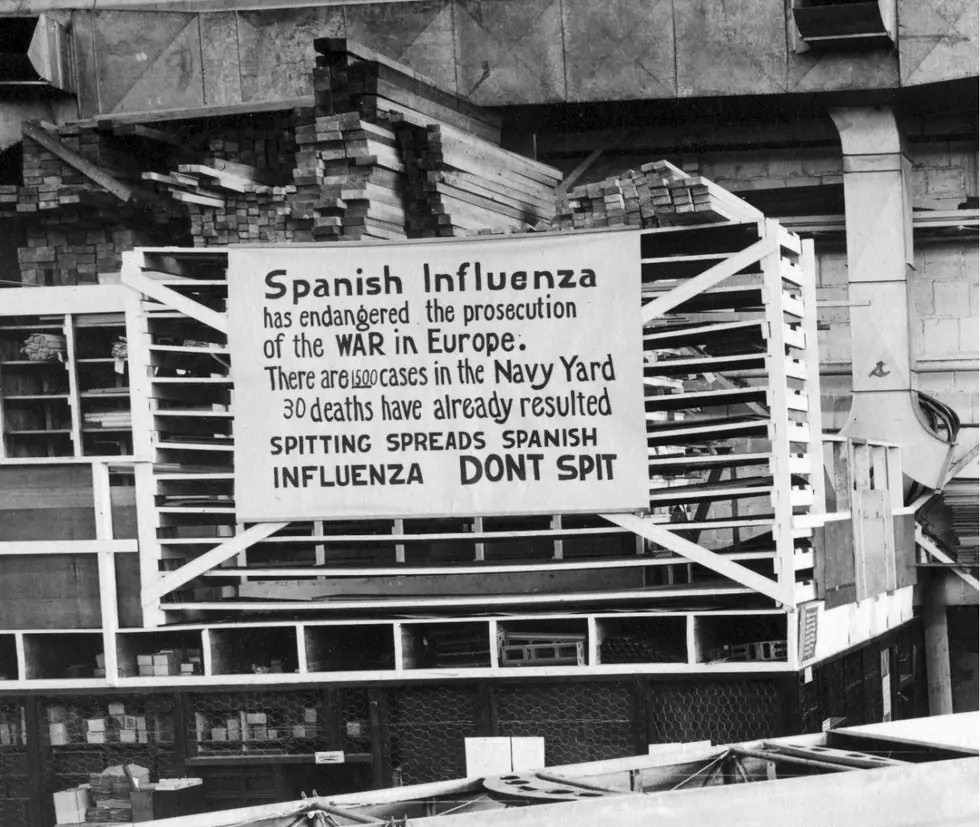

Arrests were made, she said, of individuals who refused to cover their faces in public, or those who would spit — a common action in public a century ago.

There was no vaccine to protect against influenza protection in 1918. There also were no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections related to the flu, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

So, similar to tactics being used currently to fight COVID-19, non-pharmaceutical interventions such as good personal hygiene and the use of disinfectants were encouraged. The message then, though, was printed in newspapers and on signs to be hung along roadways. Social media and news media make dispersing that message much easier in 2020.

"We will see how quickly a vaccine can be developed, rigorously tested, and dispensed," Golden said. "Experts say that it will take at least 18 months to ensure the efficacy and safety of a vaccine."

Unlike today, healthcare professionals did not have the option to treat patients with mechanical ventilators.

While the current pandemic's "demographics" won't be fully known until it clears out, Golden does see a difference in the groups targeted by the two viruses. COVID-19 appears to be deadliest among those 60 and over, or with any serious underlying medical conditions. A unique feature of the 1918 flu pandemic, according to the CDC, was the high mortality in healthy people, including those aged 20 to 40.

The 1918 pandemic produced the greatest influenza death total in recorded history, according to the CDC. In 1918, more U.S. soldiers died from the pandemic than were killed during World War I. It's estimated that about one-third of the world's population became infected with the virus.

Because of needs overseas during the war, the U.S. experienced a shortage of medical personnel to fight the pandemic.

"We've had to bring in student nurses, student doctors — then and now," Golden said.

In late March, Rutgers announced its medical school would graduate 192 students a month early so they can join the front lines fighting COVID-19.

Golden said another unfortunate similarity between the two pandemics is a quick spike in the number of deadly cases that led to space issues at morgues and funeral homes. The convenience store chain Wawa recently donated a refrigerated truck to New Jersey to help store the bodies of people who've passed in hospitals.

"I was hoping not to see that this time around," Golden said.

In the 100 years since the flu pandemic, the U.S. has made major strides in its fight to control influenza. Still, it's a yearly threat, and vaccinations available to the public may not match the strains of influenza circulating throughout the community.

Medical professionals say it's too early to tell whether the current COVID-19 emergency is a one-and-done situation, or a threat that will return on a regular basis or with certain weather conditions.

READ MORE: Inside the Meadowlands field hospital

Contact reporter Dino Flammia at dino.flammia@townsquaremedia.com.

More From New Jersey 101.5 FM