Republican Disputes Benghazi Criticism

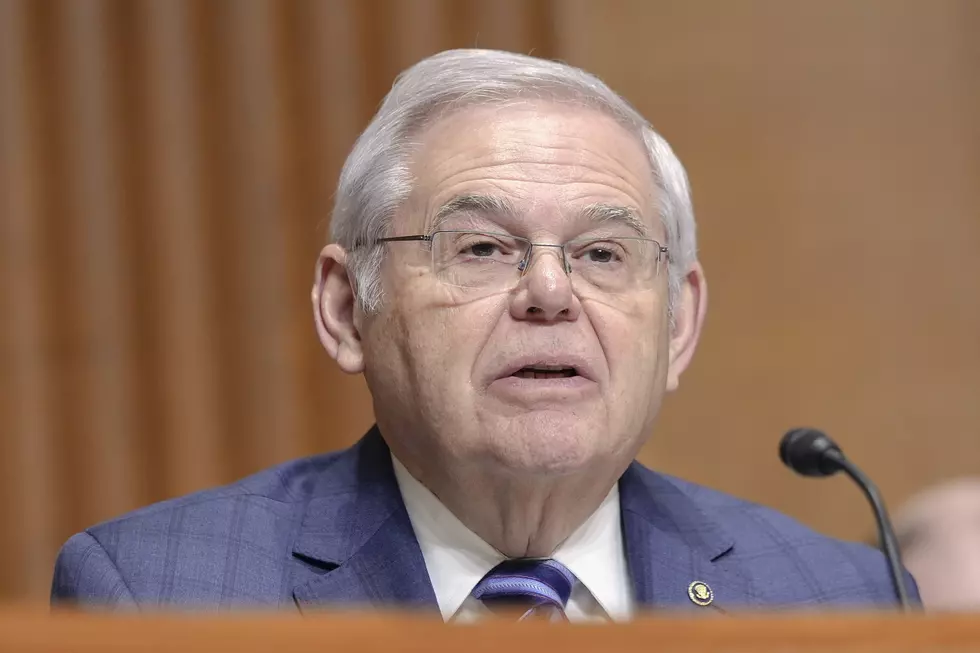

A general who was in a military operations center monitoring the deadly attack on the diplomatic compound in Benghazi told Congress Thursday that Washington didn't do enough to stop it, but his testimony was quickly disputed by the powerful chairman of the House Armed Services Committee.

Retired Brig. Gen. Robert Lovell, the star witness at a House Government Oversight and Reform Committee hearing, testified that U.S. forces "should have tried" to get to the outpost in time to help save the lives of Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans. He blamed the State Department for not making stronger requests for action.

Lovell was monitoring the attack from U.S. Africa Command's headquarters in Germany. He says it was clear that the attack was hostile action and not a protest run amok, as the Obama administration initially described it.

"Four individuals died. We obviously did not respond in time to get there," he said.

Just hours later, Rep. Howard "Buck" McKeon, R-Calif., challenged Lovell's testimony and questioned whether his presence in the U.S. military's operation center during the 2012 attack gave him a clear view of all that was going on.

"Lovell did not serve in a capacity that gave him reliable insight into operational options available to commanders during the attack, nor did he offer specific courses of action not taken," McKeon said.

The chairman said his committee had interviewed more than a dozen witnesses in the operational chain of command and reviewed thousands of pages of transcripts, emails and other documents.

"We have no evidence that Department of State officials delayed the decision to deploy what few resources the Defense Department had available to respond," McKeon said. "Lovell did not further the investigation or reveal anything new, he was another painful reminder of the agony our military felt that night: wanting to respond but unable to do so."

The unusual rebuke pitted McKeon, who has said he was satisfied that the military did all it could on Sept. 11, 2012, against fellow Republican and Californian Rep. Darrell Issa, who has doggedly pursued the question of whether the military was told to "stand down" on the night of the attacks.

Congress has concluded that the military was never told to "stand down," and that assets such as fighter jets in Italy or other help weren't ready to respond in time for the two attacks that occurred eight hours apart.

The latest furor was in reaction to a newly released email from White House deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes that shows that within days of the attack the White House embraced talking points for Susan Rice that blamed the turmoil that erupted in North African and Middle East cities in September 2012 on an anti-Islamic video.

Also at issue is why the Rhodes email, released through a Freedom of Information Act request from a conservative legal group, was not included among documents the White House released last year regarding the response to the Benghazi attack. Carney said the email referred to the upheaval and rioting throughout the region, not Benghazi in particular, even though Benghazi is briefly mentioned.

"This release through a FOIA request, you know, has revived this story, but it doesn't mean that the facts have changed. They haven't," Carney said.

House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, called on Secretary of State John Kerry to testify on why the administration did not provide the emails to Congress last year.

McKeon, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, said earlier this month that he was satisfied with how the military responded, considering where troops were based and how the two separate attacks unfolded.

Lovell described the mood in Africa Command during the attack: "It was desperation to gain situational awareness."

The Obama administration initially described the attack as a response to the video that had sparked protests at the U.S. Embassy in Cairo and elsewhere. Susan Rice, then the U.N. ambassador, went on Sunday television talk shows and described it as such. Those comments have stirred up political opposition ever since, as military and other officials have said it was clear it was a terror attack unrelated to the video.

Lovell told the committee it was clearly not an attack borne of the protests.

The U.S. has not yet identified those responsible but now believes it was done by Islamist militants who set fire to the diplomatic outpost and engaged Stevens' security officials and others in gunfire. Stevens died of smoke inhalation in a safe room in the diplomatic compound. The diplomats were aided by officials from the CIA outpost a mile away.

A Republican congressman is drafting legislation to give the military and intelligence agency the authority to kill those responsible for the attack. Rep. Duncan Hunter of California said Thursday that he will try to add his bill to the annual defense policy legislation when the House Armed Services Committee considers the measure on Wednesday.

Hunter said his legislation is the same as the authority that the Congress gave the government after the Sept. 11 attacks.

"I don't know why they don't ask for it. They must not care," Hunter said in an interview. "It shouldn't take Congress to do this. They should have asked for this right after the attacks."

Hunter said his legislation was prompted by closed-door testimony from Gen. Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who told the panel in October that the U.S. cannot strike the perpetrators under the authorization for use of military force, the 2001 law that applies to terrorists.

More From New Jersey 101.5 FM